Pomegranate Trees

My mother died in 1983. It was sudden and yet expected as she had a blood transfusion 15 years earlier tainted with Hepatitis C. It lurked silently in her body for all those years, and then reared its head, and in a few months, she was gone.

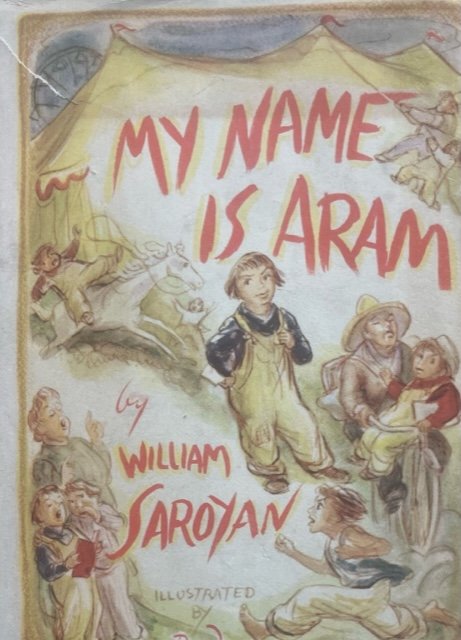

Shortly after my mother passed, I was visiting with my father and sitting in the kitchen of my childhood home with him. I, myself, had a 2-year old and was starting a new life 40 miles away. My father had just received a present from a grateful patient expressing sympathy for the loss of his wife of three decades. It was a book called “My name is Aram“ by William Saroyan.

Over the years, my father had shared his love of poetry with me. He initiated in my heart a great respect for classic and fine writing. An English literature major in college, I found this mutual appreciation, a worthy refuge in our shared grief. He opened the book. It was a collection of short stories, and the one he chose to read aloud that evening was “The Pomegranate Trees“.

Now, 40 years later, that vision in the kitchen comes to mind. I vividly remember the watercolor painting on the cover of the book and the name of that story.

So, I look online and find a version of The Pomegranate Trees that was written for The Atlantic in 1938. I sit down with great respect and awe on this quiet morning in May and read.

The story is poignant and humorous and direct. Like my father. It’s the story of a desolate acreage in the Sierra Nevada foothills that was all desert. Though the land was barren, the narrator (an eleven yr old boy) has an uncle with dreams…big dreams! He purchases the 630 acres and entertains dreams of planting and paradise. Over the course of the story, the boy and his uncle work the land, and eventually lose their ability to continue to pay for it after investing in tractors and trees and field hands and well diggers.

After selling the land and several years passing, the uncle and the boy drive by the property. The final sentences in the story read:

“The trees were all dead. The soil was heavy again with cactus and desert brush. Except for the small dead pomegranate trees the place was exactly the way it had been all the years of the world. We walked around in the orchard for a while and then went back to the car.

We got into the car and drove back to town. We didn’t say anything because there was such an awful lot to say, and no language to say it in.”

It is only now, right here, decades after my mother’s and father’s deaths, and the adventure of sitting in the kitchen with my father reading aloud to me as a young adult, that I realized the depth of his sorrow and the way that his own grief prevented him from knowing how to speak. It was only through the story that he was reading to me that he could communicate how much he loved my mother and how deeply he felt her loss.

In reflection, the tears are falling, and the truth of a life well- lived and dreams held and dissolved, and all of the dimensions of experience that a heart can endure, were in that moment. I am in deep deep gratitude to what I have been given in my own heart as tears are so rare of late and yet, I’m so grateful when they come.